Introduction

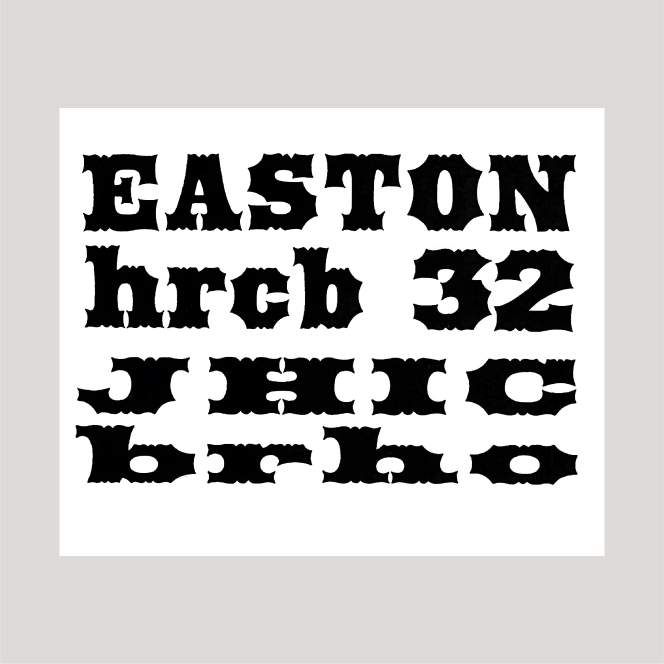

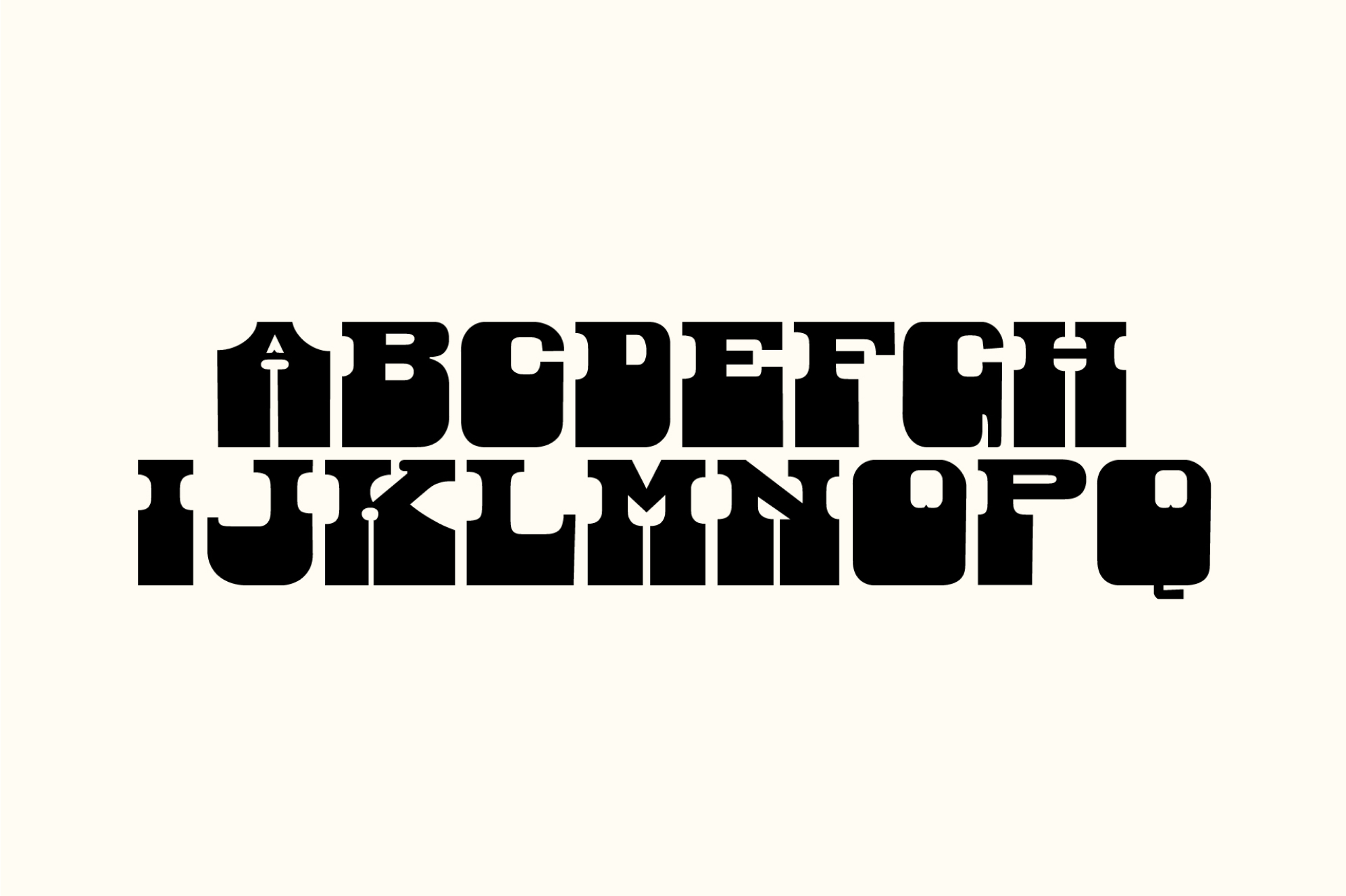

Drawing inspiration from the iconic 'Danfo' buses of Lagos, Nigeria, Danfo is a Tuscan slab serif that merges design elements from Western and local traditions. This single-weight font features striking ornamental details through variable axes, demonstrating technical and construction ingenuity. It also serves as a documentation of Lagos' vibrant visual culture.

Trouble no

get horn

Aşîtî

+234-(0)80-1569-AFRO Danfo234@gmail.com

hãy tự do

AŞÎTÎ

MOVE

+234*

Afro-latin Support

Danfo supports the Google Latin Core, Plus, Vietnamese and African character sets, including but not limited to Swahili, Zulu, Hausa, Yoruba, and Shona.

Sa'an nan Abu Sufyan ya isa, yana gaya wa Kinana ya ajiye baka don su iya tattauna batun hankali.

Sa'an nan Abu Sufyan ya isa, yana gaya wa Kinana ya ajiye baka don su iya tattauna batun hankali.

STYlISTIC ALTERNATES

Große Gefühl

Große Gefühl

Cuộc phiêu lưu

Cuộc phiêu lưu

Jövőbeli

Jövőbeli

LANGUAGE SUPPORT

821 languages available

Africa

475 Languages

Abidji, Abron, Adangme, Adara, Adele, Afar, Afrikaans, Agatu, Aghem, Agwagwune, Ahanta, Aja, Akan, Alago, Anii, Anufo, Anyin, Arabic (Chadian Spoken), Ashe, Asu, Avatime, Avokaya, Awak, Ayizo Gbe, Baatonum, Bacama, Bafia, Baga Sitemu, Baka, Bali, Bambara, Bamun (Latin), Bana, Banda (West Central), Bandi, Bangwinji, Baoulé, Bapuku, Bari, Basa, Basaa, Bassa, Bassari, Bedawiyet, Bedjond, Bekwarra, Belanda Viri (Latin), Bemba, Bena, Bench, Beng, Benga, Berom, Bete-Bendi, Bété (Guiberoua), Bhele, Bilen, Bimoba, Bini, Birifor (Southern), Bisã, Bissa, Boko, Bokobaru, Buamu, Budu, Bulu, Bura-Pabir, Burak, Bushi, C’Lela, Cahungwarya, Cakfem-Mushere, Central Atlas Tamazight, Central-Eastern Niger Fulfulde, Cerma, Chiduruma, Chiga, Chokwe, Chumburung, Cishingini, Comorian (Latin), Comorian (Ngazidja), Crioulo (Upper Guinea), Cwi Bwamu (Latin), Daba, Dadiya, Dagaare (Southern), Dagbani, Dangaléat, Dawro, Dazaga, Deg, Delo, Dendi, Denya, Dghwede, Dida (Yocoboué), Didinga, Dikaka, Dinka, Dinka (Northeastern), Ditammari, Dogon (Toro So), Doyayo, Duala, Duya, Dyula, Dza, Ebira, Ede Cabe, Ede Ica, Ede Idaca, Ede Ije, Ejagham, Elip, Embu, Engenni, English, Etkywan, Etulo, Ewe, Ewondo, Ezaa, Fe’fe’, Fon, Foodo, French, Fulah, Fulfulde (Adamawa), Fulfulde (Borgu), Fulfulde (Western Niger), Fuliiru, Fur, Ga, Gamo, Ganda, Gbari, Gbaya (Sudan), Gbaya-Mbodomo, Gbe (Tofin), Gbe (Waci), Gbe (Xwela), Gen, German, Gikyode, Godié, Goemai, Gofa, Gokana, Gonja, Gor, Gourmanchéma, Gude, Gumuz, Gun, Gungu, Gusii, Gwak, Gyele, Hanga, Hausa, Hdi, Hyam, Ibani, Ibibio, Igbo, Igede, Igo, Ijo (Southeast), Ik, Ika, Ikposo, Ikwere, Ikwo, Iten, Ivbie North-Okpela-Arhe, Izere, Izii, Jibu, Jola-Fonyi, Jola-Kasa, Jukun Takum, Jur Modo, Kabalai, Kabiyé, Kabuverdianu, Kabyle, Kalenjin, Kamba, Kamuku, Kamwe, Kanuri, Kanuri (Central), Kanuri (Manga), Kaonde, Karaboro (Eastern), Karang, Karekare, Kasem, Kenga, Kenyang, Kibaku, Kikuyu, Kimbundu, Kimré, Kinyarwanda, Kirike, Kissi (Northern), Kituba, Koma, Kombe, Kongo, Konjo, Konkomba, Koonzime, Kouya, Koyra Chiini, Koyraboro Senni, Kpelle (Guinea), Krache, Krio, Krumen (Plapo), Krumen (Tepo), Kuanyama, Kukele, Kunama, Kuo, Kuria, Kusaal, Kutep, Kutu, Kwanja, Kwasio, Kwere, Lama (Togo), Lamang, Lamnso', Langi, Lele, Lendu, Lese, Ligbi, Limba (West-Central), Limbum, Lingala, Lobala, Lobi, Logo, Lokaa, Loko, Longuda, Lozi, Luba-Katanga, Luba-Lulua, Lugbara, Luguru, Lukpa, Lunda, Luo, Luvale, Luwo, Luyia, Lyélé, Maasina Fulfulde, Machame, Makaa, Makhuwa, Makhuwa-Meetto, Makonde, Malagasy, Malay (Latin), Mamara Senoufo, Mambila (Cameroon), Mambila (Nigeria), Mampruli, Mandingo, Mandjak, Mangbetu, Maninka (Sankaran), Maninkakan (Eastern), Masai, Mauritian Creole, Mbe, Mbelime, Mbembe (Cross River), Mbo, Mbuko, Mbula-Bwazza, Me’en, Mende, Ménik, Merey, Meru, Meta’, Mina, Miyobe, Mmaala, Moba, Mokole, Morokodo, Mossi, Mumuye, Mundang, Mundani, Mündü, Muyang, Mwaghavul, Mwan, Mwani, Nafaanra, Nama, Nara, Nateni, Nawdm, Nawuri, Ndamba, Ndogo, Ndonga, Ngambay, Ngangam, Ngas, Ngbaka, Ngbandi (Northern), Ngiemboon, Ngindo, Ngiti, Ngomba, Ngulu, Nigerian Fulfulde, Nigerian Pidgin, Ninzo, Nkonya, Nomaande, Noone, North Ndebele, Northern Dagara, Northern Sotho, Ntcham, Nuer, Nugunu, Nuni (Northern), Nupe-Nupe-Tako, Nyabwa, Nyamwezi, Nyanja, Nyankole, Nyemba, Nzima, Obolo, Ogbah, Okiek, Oromo, Otuho, Paasaal, Pangu, Parkwa, Pero, Pogolo, Pökoot, Portuguese, Pulaar, Pular, Pyam, Rendille, Reshe, Réunion Creole French, Rigwe, Rombo, Ron, Rundi, Rwa, Saafi-Saafi, Samburu, Sango, Sangu, Sãotomense, Saxwe Gbe, Sekpele, Selee, Sena, Sénoufo (Djimini), Sénoufo (Supyire), Serer, Seselwa Creole French, Shambala, Sheko, Shilluk, Shona, Sisaala (Tumulung), Sissala, Siwu, Soga, Sokoro, Somali, Soninke, South Ndebele, Southern Nuni, Southern Sotho, Spanish, Suba, Sudanese Arabic, Sukuma, Suri (Tirmaga-Chai), Susu, Swahili, Swati, Tachelhit (Latin), Taita, Takwane, Tal, Talinga-Bwisi, Tamasheq (Latin), Tampulma, Tangale, Tarok, Tasawaq, Tedaga, Téén, Tem, Tera, Teso, Tiéyaxo Bozo, Tikar, Timne, Tiv, Toma, Tonga, Toura, Toussian (Southern), Tsikimba, Tsishingini, Tsonga, Tsuvadi, Tswana, Tula, Tumbuka, Tunen, Tuwuli, Umbundu, ut-Hun, ut-Ma’in, Vagla, Vai (Latin), Venda, Vengo, Vunjo, Vute, Waama, Waja, Wan, Wandala, Warji, Wè Northern, Wolaytta, Wolof, Xhosa, Yala, Yalunka, Yamba, Yambeta, Yangben, Yao, Yaouré, Yasa, Yom, Yoruba, Zande, Zarma, Zayse, Zigula, Zulgo-Gemzek, and Zulu.

AMERICAS

128 Languages

Achuar-Shiwiar, Aguaruna, Aleut, Amahuaca, Amarakaeri, Arabela, Arapaho, Asháninka, Ashéninka Perené, Ashéninka (Pichis), Awa-Cuaiquer, Aymara, Bora, Candoshi-Shapra, Caquinte, Cashibo-Cacataibo, Cashinahua, Central Alaskan Yupik, Central Mazahua, Chachi, Chayahuita, Chickasaw, Chimborazo Highland Quichua, Chinantec (Chiltepec), Chinantec (Ojitlán), Cofán (Latin), Colorado, Crioulo (Upper Guinea), Danish, Delaware, Dutch, English, Epena (Latin), Ese Ejja, Filipino, French, Garifuna, German, Guadeloupean Creole French (Latin, Martinique), Guarani, Guarayu, Guianese Creole French, Gwichʼin, Haitian Creole, Hawaiian, Hindustani (Sarnami), Hopi, Huastec (San Luís Potosí), Huitoto (Murui), Innu, Italian, Jamaican Creole English, Kaingang, Kalaallisut, Kaqchikel (Central), Kituba, Kulango (Bouna), Kʼicheʼ, Lakota, Lushootseed, Mam, Mapuche, Matsés (Latin, Peru), Mazatec (Ixcatlán), Mi'kmaq, Mískito, Mixe (Totontepec), Mixtec (Metlatónoc), Mohawk, Moro, Muscogee, Nahuatl (Central), Navajo, Nomatsiguenga, Otomi (Mezquital), Páez, Papiamento, Pipil, Portuguese, Purepecha, Q'eqchi', Quechua, Quechua (Ambo-Pasco), Quechua (Arequipa-La Unión), Quechua (Ayacucho), Quechua (Cajamarca), Quechua (Cusco), Quechua (Huamalíes-Dos de Mayo Huánuco), Quechua (Huaylas Ancash), Quechua (Margos-Yarowilca-Lauricocha), Quechua (North Junín), Quechua (Northern Conchucos Ancash), Quechua (South Bolivian), Quechua (Unified Quichua, old Hispanic orthography), Romany, Saint Lucian Creole French (Latin), Secoya, Seri, Sharanahua, Shipibo-Conibo, Shuar (Latin, Ecuador), Siona, Spanish, Sranan Tongo, Straits Salish (Latin), Tenango Otomi (Latin), Ticuna, Toba, Tojolabal, Totonac (Papantla), Tzeltal (Oxchuc), Tzotzil (Chamula), Uduk, Urarina, Vietnamese, Waorani, Wayuu, Welsh, Xavánte, Yagua, Yaneshaʼ, Yanomamö, Yucateco, Záparo, Zapotec, Zapotec (Güilá), Zapotec (Miahuatlán), and Zuni.

ASIA

83 Languages

Achinese, Albanian, Amis, Ao Naga, Assyrian Neo-Aramaic (Latin), Azerbaijani, Balinese, Batak Toba, Betawi, Bikol, Bodo (Latin), Brahui (Latin), Buginese, Cebuano, Central Dusun, Chavacano (Latin, Philippines), Chin (Falam), Chin (Haka), Chin (Matu), Cuyonon (Latin), Dimli, Drung, English, Filipino, French, Galo (Latin), Gelao (Klau), German, Hani, Hiligaynon, Hmong Njua, Hmong (Northern Qiandong), Hmong (Southern Qiandong), Hungarian, Iloko, Indonesian, Jarai (Latin), Javanese, Kazakh (Latin), Khasi, Kirmanjki, Kurdish (Latin), Ladino (Latin), Madurese, Malay, Maranao (Latin), Minangkabau, Mizo (Latin), Musi (Latin), Muslim Tat (Latin), Oroqen, Paite Chin (Latin), Pampanga, Polish, Portuguese, Rejang, Rinconada Bikol, Rohingya (Latin), Romani (Balkan), Romanian, Romany, Salar, Sasak, Serbian (Latin), Southern Tujia, Spanish, Sundanese, Tajik (Latin), Talysh (Latin), Tedim Chin, Tetum, Tetun Dili, Tsakhur (Latin), Turkish, Turkmen (Latin), Uab Meto, Uyghur (Latin), Uzbek, Vietnamese, Wancho Naga (Latin), Waray, West Albay Bikol, and Zhuang.

EUROPE

107 Languages

Albanian, Aragonese, Aromanian, Arpitan, Asturian, Bashkir (Latin), Basque, Belarusian (Latin), Bosnian, Breton, Catalan, Colognian, Cornish, Corsican, Crimean Turkish, Crioulo (Upper Guinea), Croatian, Czech, Danish, Dutch, English, Esperanto, Estonian, Extremaduran, Faroese, Finnish, Finnish (Kven), French, Friulian, Gagauz, Galician, German, Gheg Albanian, Hungarian, Icelandic, Inari Sami, Indonesian, Interlingua, Irish, Italian, Jèrriais (Latin), Kalaallisut, Karelian, Kashubian, Ladin, Latgalian, Latin, Latvian, Ligurian, Lithuanian, Livonian, Lombard, Low German, Lower Sorbian, Lule Sami, Luxembourgish, Maltese, Manx, Middle High German, Mirandese, Neapolitan, Northern Frisian, Norwegian Bokmål, Norwegian Nynorsk, Occitan, Old English, Old French, Old High German, Old Irish, Old Norse (Latin, Sweden), Old Provençal, Old Welsh (Latin), Oroqen, Picard, Piedmontese, Polish, Portuguese, Romagnol, Romani (Balkan), Romanian, Romansh, Romany, Sardinian, Sassarese Sardinian, Saterland Frisian, Scottish Gaelic, Serbian (Latin), Sicilian, Silesian, Slovak, Slovenian, Southern Sami, Spanish, Swedish, Swiss German, Tatar (Latin), Turkish, Uncoded languages (Latin, World), Upper Sorbian, Venetian, Veps, Võro, Walloon, and Walser.

OCEANIA

28 Languages

Bislama, Chamorro, Chin (Haka), Chuukese, Cook Islands Māori, English, Fijian, French, Gilbertese, Italian, Maori, Marshallese, Niuean, Palauan, Pijin, Pintupi-Luritja, Pohnpeian, Rapa (Latin), Samoan, Tahitian, Tiwi (Latin), Tok Pisin, Tokelau, Tongan, Tuvalu, Wallisian, Warlpiri, and Yapese.

Get Danfo

Danfo is a tuscan serif font inspired by vinyl stickers on the

ubiquitous Danfo buses of Lagos. It combines design features from

both traditions and unites them in a contemporary family. The

versatile system consists of eighty-four styles across six widths

and seven weights.

Danfo is tuscan serif font inspired by vinyl stickers on the

ubiquitous Danfo buses of Lagos. It combines design features from

both traditions and unites them in a contemporary family. The

versatile system consists of eighty-four styles across six widths

and seven weights.

Part 1 - Research

Written by Seyi Olusanya and Ife Adegbie

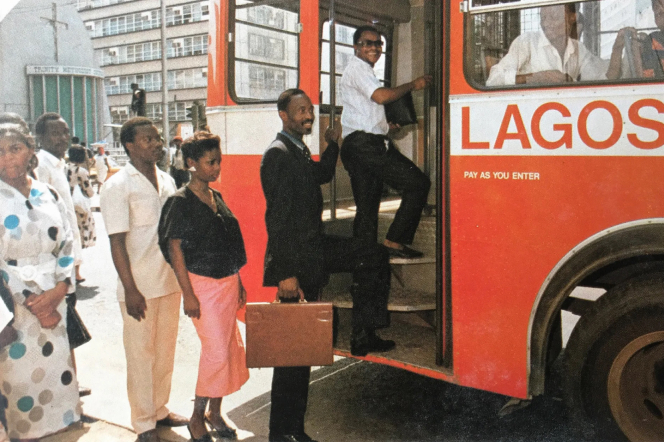

The life of a city is represented in different ways. Every city has a visual language. New York has Times Square and yellow cabs, and London has Big Ben and black taxis. For Lagos, it is its yellow buses.

↳ From Trams to “Kia Kia” Buses

Lagos only started experiencing significant innovation in

mechanical transportation in the late 19th century. Before

then, the colony was considered compact enough for

distances to be covered by non-mechanical transportation.

An economic boom between 1918 and 1920 led to urban

sprawl, empowered Lagosians with resources to purchase

motor cars, and led to more foot traffic that pressured

the colonial government to pay more attention to public

transportation infrastructure.

The government first attempted to solve commute problems

by installing an electric tram that linked the island to

the mainland. It wasn’t successful and ran at a loss up

until 1933. Ferry services between Apapa and the island,

the government’s second attempt, took off in 1925. This

also ran at a terrible loss due to the failure to recoup

investment capital and the underhand dealings of the

people in charge.

In 1928, the Lagos Town Council (LTC) announced that

private individuals/enterprises with buses could apply for

licenses permitting them to legally ply the crowded routes

of Ebute Metta to Yaba and, eventually, Agege. This

eventually led to the inauguration of Lagos’ first

regulated bus service in collaboration with J.N

Zarpas.[Fig. 2]

Zarpas ran what other bus license applicants would

consider a monopoly for about 30 years before being

acquired in 1958 by the LTC.

At this time, immense human and vehicular growth put much pressure on roads, gradually damaging them— the beginning stages of the notorious Lagos traffic jam. This eventually led to the conversion of some streets to one-way roads, mostly plied by impatient drivers. These developments, combined with the inefficiencies of the LTC’s bus systems after the acquisition, led to new buses called “kia kia buses” appearing more frequently on the roads. These yellow imported Volkswagen buses were famous for speed and access to routes that more formal, government-regulated buses couldn’t travel. They were also cheaper because of the frequency of trips and their miserly approach to vehicle maintenance.(1) They took off.

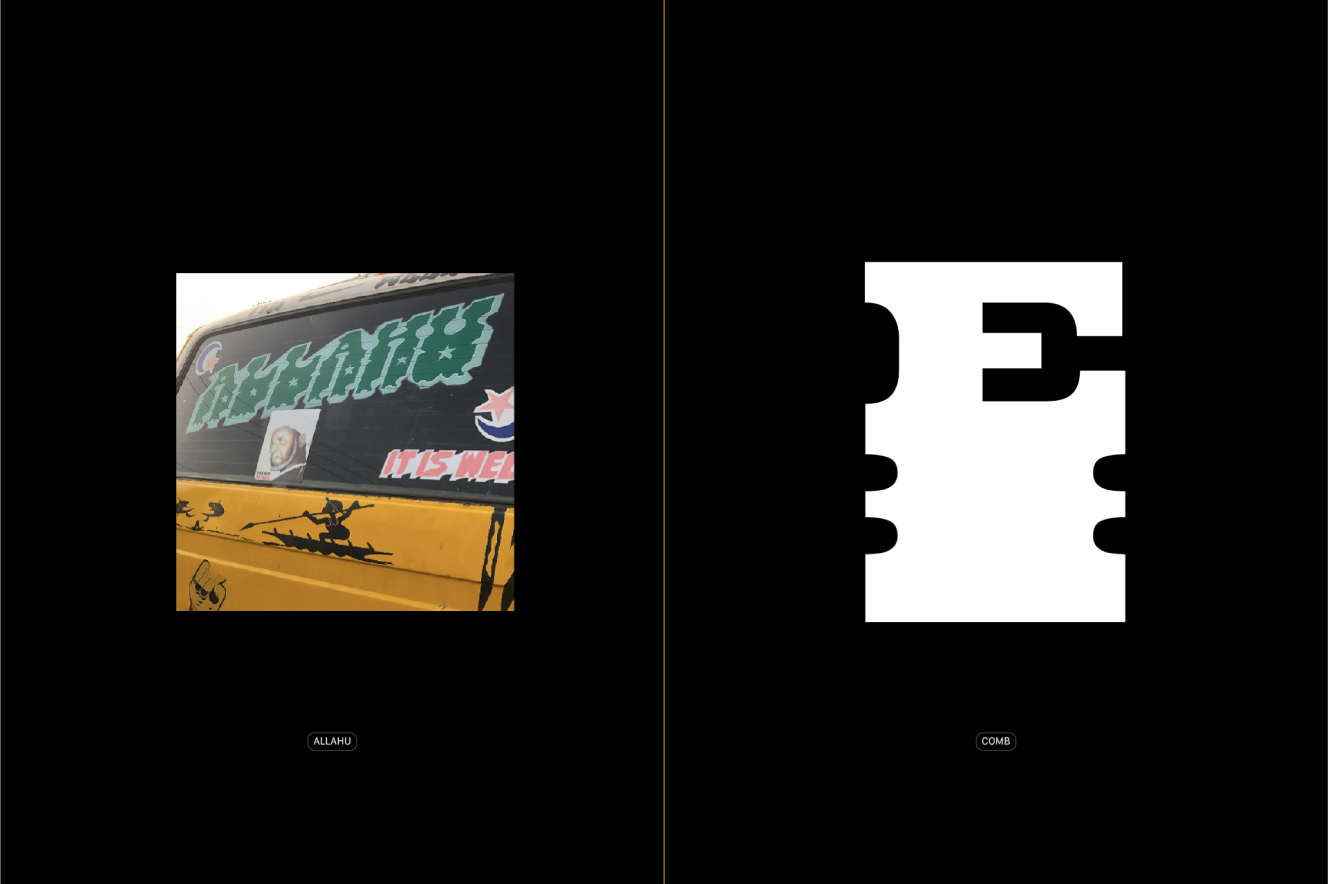

↳ Sticker Culture

Adorning the bodies of Danfos are vinyl stickers,

inscriptions, paint jobs, lights and more whose content,

style and placement are based on their owners' personal

beliefs, identity and self-expression.

As Nigerians began white-collar jobs, their purchasing

power increased, and owning a vehicle became more common.

Vehicle owners outfitted their vehicles with stickers for

aesthetic purposes, religious alliance, and to signal

class mobility.[Fig. 3]

As the gap for public transportation persisted, private

individuals began using their vehicles for popular

commercial routes, kickstarting the use of inscriptions

for identification purposes as the private commercial

vehicles at the time bore basic descriptive inscriptions

such as ‘goods only’, ‘private’ or ‘goods or owner’s

risk.’(2)

Some of the earliest vehicles with inscriptions were the

Bolekajas, which roughly translates to “come down and

let's fight”. They were made from Bedford bus heads and

wooden compartments with a single exit and entrance, often

resulting in discomfort. Some of these were branded with

hand-painted company names.[Fig. 4]

As these private entities adopted larger vehicles like the

molue and bolekaja, their inscription use further evolved

to inscriptions of self-expressions such as behavioural

traits, life experiences, and more.(3)

Religious symbols, mantras, and pop culture references

like football affiliations and musical alliances,

signalled via stickers, spark a playful rivalry between

drivers.

While the English language may be the basis for

transliteration and alphabetical phonetics, the content is

still largely Nigeria-centric, often being written in

local languages and pidgin; Fálànà gbó̩̩ tìe̩(Mind your own

business), Igi á rúwé (The tree will sprout leaves), ‘Why

worry’, ‘Sea Never Dry’, Nagode Allah (Thank you God), and

‘Man go wack’ among other inscriptions were in use,

especially between the 60s and mid 70s.

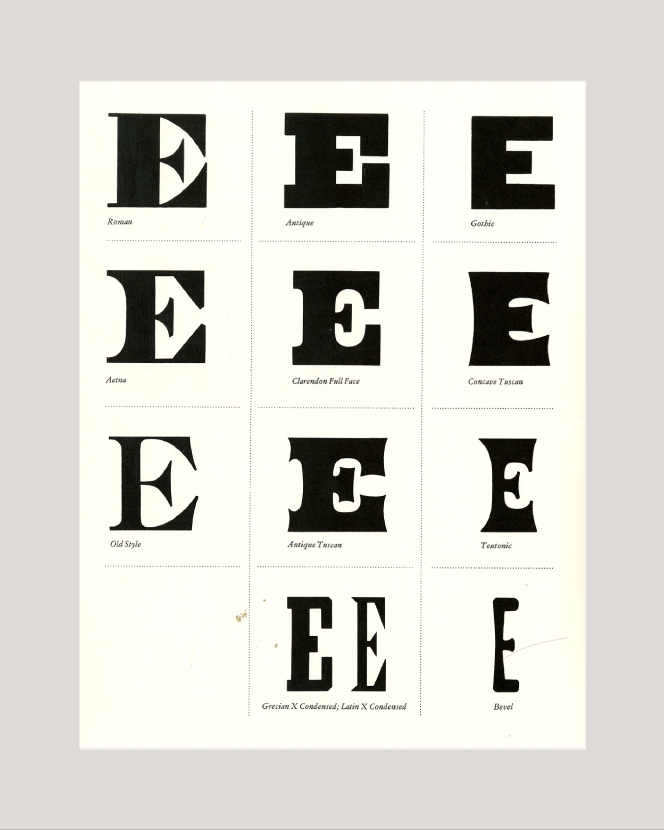

↳ Tuscan Influences

The design language of these buses has been extensively

researched, reporting an evident pattern to the decorative

style of Danfos. A particularly striking feature; the

typography employed for danfo adornments, has caught the

eyes of many across the globe. As typefaces evolved,

foundries dedicated to printing and typography became

commonplace, particularly in Europe. Amongst the multiple

typefaces imported into Nigeria, the Tuscan ‘Western style

font’ dominates the danfo design scenery.

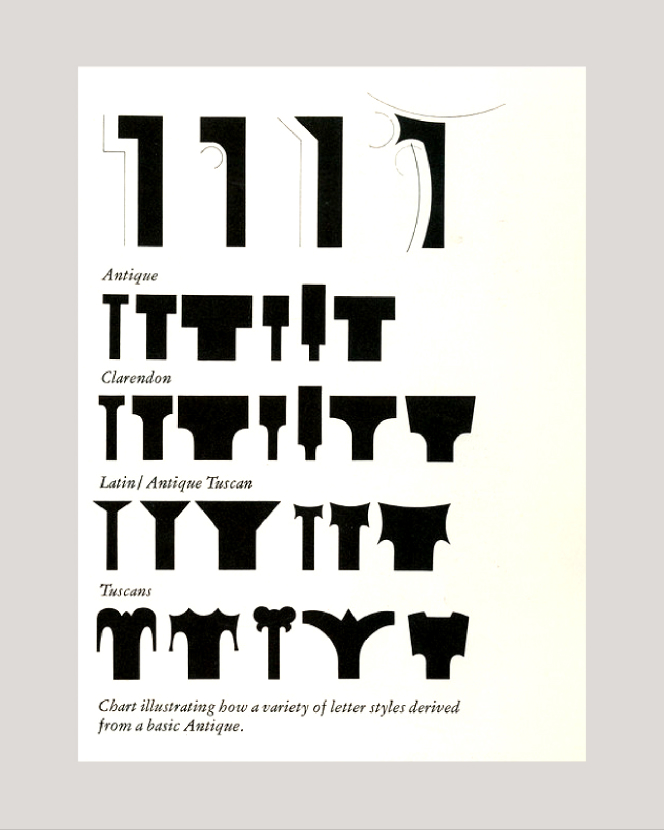

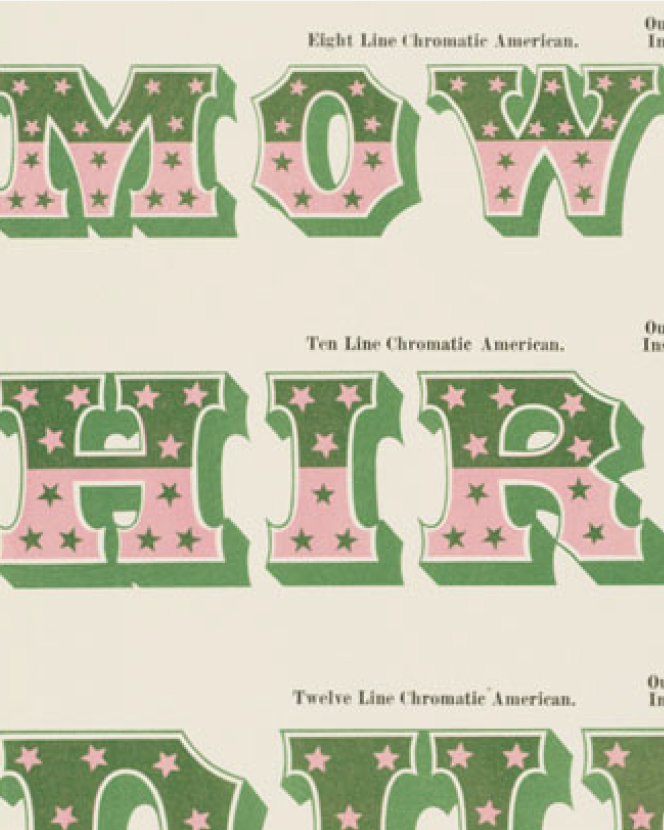

Popular in the Victorian era, the Tuscan style was applied

to various typefaces. English foundries adopted the Tuscan

style as synonymous with ornamental and focused on its

decoration instead of readability. It is an approach to

type design with one or a combination of bi or trifurcated

ends, symmetrical spurs in the middle of the letter and

ornamental additions (drop shadows, patterned interior).

Their further distinctions can be determined based on the

source categories: gothic, roman and plain. It is often

uncial (capital letters alone), and this specific

characteristic is maintained within the Nigerian design

sphere.

Due to a lack of documentation, the exact timeline for transferring this design knowledge to Nigeria cannot be narrowed. The famous history of typeface printing in Nigeria can be linked to the invention of commercial-scale wood types in New York in 1828. The typefaces used were British and imported from England.(4) Coupled with the information transfer stemming from WW2, American influence on typography in Nigeria is undeniable.

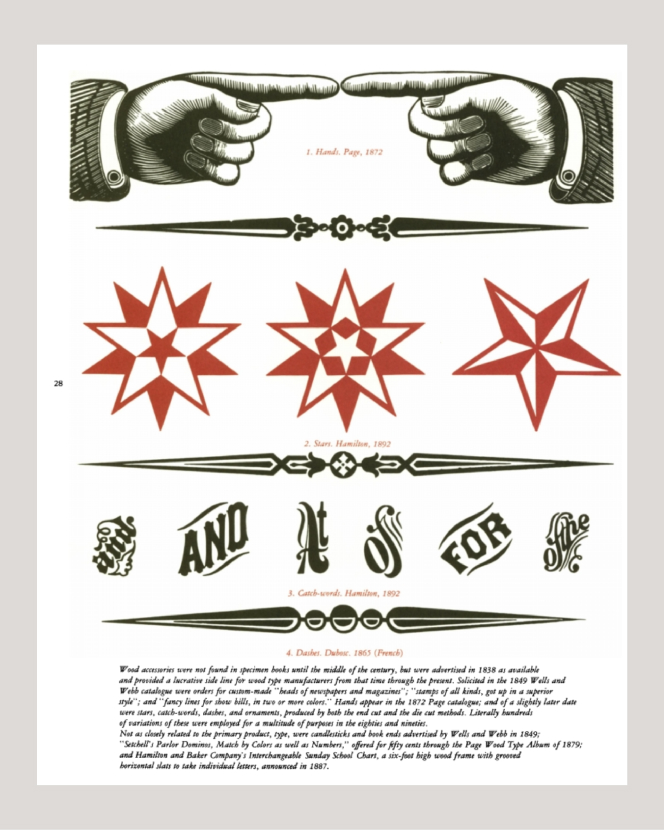

↳ Decorative Details

Wood-type accessories were initially created as additional characters accompanying standard character sets. Some of the earliest accessories were drawn as stand-alone deliverables for Newspaper and magazine mastheads. American wood-type designers started offering these add-on services in the 1830s.

While the basic structure of the Tuscan remains, it has been stylised to cater to Nigerian tastes. The star font finish, common in American design, is often seen alongside Nike, afro comb, and mosque silhouette finishes. The accessories can be as diverse as the messaging.

↳ Vinyl Stickers

Inscriptions on vehicles were primarily painted in the 60s and 70s and are still common, particularly with larger vehicles like lorries and trailers. However, with the flexibility and ease of use of vinyl stickers, their use is more pronounced. They gained prominence in the early 80s owing to rapid technological advancement in the country. As a result, they can be found everywhere. Print shops serve this purpose, mimicking the functions and structure of old English foundries.

Lettering is recreated and redesigned based on the needs of the customer/driver. Although they often serve both vinyl and paint needs, vinyl pays more due to its high rate of use and application time. Knowledge transfer among designers is operated in an informal apprenticeship manner, which still exists today. Individuals interested often begin tutelage under the shop’s head/leading printer, who trains and gives them jobs.

Their methods are often passed down orally across generations, leading to a lack of steady documentation on processes.(6) Trained students often go on to begin their shops, branch out to other forms of printing (e.g. business cards, etc.), and in some cases, begin mobile print shops, as seen below.

References

- Ayodeji, Olukoju, Infrastructure Development and Urban Facilities in Lagos, IFRA-Nigeria, 2003.

- Innocent, Chiluwa, Religious vehicle stickers in Nigeria: A discourse of identity, faith and social vision, 2008, pp 373-374.

- Jordan, 2008, Van Der Geest, 2009.

- Lorraine Ferguson, and Douglass Scott. “A Time Line of American Typography.” Design Quarterly, no. 148, 1990, pp. 23–54. JSTOR.

- Kelly, Rob Roy. “American Wood Type.” Design Quarterly, no. 56, 1963, pp. 1–40. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/4047285. .

- Mr Samuel, print shop owner

Images

- https://www.dreamstime.com/heart-obalende-bus-stop-panoramic-yellow-buses-waiting-to-load-passengers-to-their-respective-destinations-image163444709

- https://medium.com/forafricans/faba-vintage-a-glimpse-of-lagos-olden-days-4f41e3c63890

- https://nigerianostalgia.tumblr.com/post/38276002425/unknown-man-in-his-car-1970s-more-vintage?

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wood_type#:~:text=In%20letterpress%20printing%2C%20wood%20type,large%20sizes%20of%20metal%20type.

- https://twitter.com/ScrollnQuillHub/status/809434136880513025

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XTmnfg8mhyI&t=337s

- © Dá Design Studio

- © Dá Design Studio

- © Dá Design Studio

- Kelly, Rob Roy. “American Wood Type.” Design Quarterly, no. 56, 1963, pp. 86

- Kelly, Rob Roy. “American Wood Type.” Design Quarterly, no. 56, 1963, pp. 87

- 1858 Specimens of Wood Type, D. Knox & Co., Fredericksburg, Ohio. Held at the John M Wing Foundation, Newberry Library, Chicago, Illinois.

- Synagogue, Ikotun, Lagos, November 1, 2014.

- Unknown

- Wm. H. Page & Co. Specimens of chromatic wood type, borders, etc. manufactured by Wm. H. Page & Co. Greeneville, Conn. : The Co., 1874. Electronic reproduction. New York, N.Y. : Columbia University Libraries, 2013. NNC. Columbia University Libraries Electronic Books. 2006.

- © Dá Design Studio

- © Dá Design Studio

- © Dá Design Studio

- © Afrotype

- © Afrotype

- © Afrotype

- © Afrotype

- © Afrotype

Part 2 - Design

Written by Seyi Olusanya

Danfo buses, typically converted Volkswagen vans, are known for their yellow paint, energetic conductors, and serving as a vital and chaotic form of public transportation in Lagos, Nigeria.

↳ The First Version (2018)

Danfo's first version was born out of curiosity and a need

for more representation. I had been boarding local

transportation for most of my life and found the aesthetic

and messaging fascinating. Over time, I began to ask

questions. Why isn’t there a documented digital version of

this typeface? why is the messaging usually religious or

referencing pop culture? Who sets them? Where are they

made?

I wanted to build a personal brand that championed

local design and made it more accessible. II spent the

next few months visiting bus parks, taking pictures,

sketching and eventually digitising the first version of

Danfo on a cracked version of FontLab. I had no formal

training in type design. I completed this version

[Fig. 2] fueled

purely by the desire to finish what I’d started. It was

received decently and even got some local and

international coverage.

↳ Another Try?

Fast-forward to 2022. I had been running a design studio, Dá, for several years. I always thought of refining the first version of Danfo, but I never quite got to it. I eventually took a stand and brought my team members on the project. I asked Johnson and Seun to visit the bus parks closest to their homes, take pictures, speak to the drivers, and find the lettering artists who make these stickers [Fig 3-11]. One fascinating realisation is that every set is different, even when cut by the same artist. After taking dozens of images, we realised two broad classifications: the complex cuts we call “rugged”, usually adorned with extra cuts and embellished with ornaments and the more straightforward, less detailed cuts that we describe as "simpu".

↳ Initial Drawings

Google Fonts reached out, and I built a team with David and Eyiyemi. The questions became more sophisticated with the added pressure of a timeline and the robust, new-found knowledge we had gotten from the books, courses, and mentors Google provided us. How do we balance the tension between antique Tuscans' traditional precision and local lettering artists' hand-cut irregular aesthetic? Did we want shadows? We had to find a balance. The initial drafts were clinical and inauthentic. We visited a major bus park in Lagos, Ojota, to work hands-on with a typesetter/lettering artist to see what we could learn.

↳ Real-Time Design with Abu

We got to Ojota bus stop and found Abu. He was hired to cut A-Z, 1-9 and some punctuation marks. His primary tools were vinyl sticker sheets in blue, yellow, and green and scissors. He cut a rectangular shape as the primary guide for the glyph space, and then he’d use this cut-out as a template for other letters. We also noticed some details in how he cut bilaterally symmetrical letters. He’d fold the glyph space sheet and then cut. We scanned the stickers and began redrawing our letters, looking for distinctive qualities we could keep.

↳ Back to the Drawing Board

We started redrawing the letters and noticed they were even more inconsistent than the initial set. After studying some more, we noticed peculiarities in the cut of the letters. There was an upwardly curved point in some letters with bilateral symmetrical counter spaces in the O and Q. We also noticed an exceptional approach to spur in the G . We decided to follow the more consistent, slightly traditional construction from the more consistent language in some pictures we took earlier for general letterform construction while exaggerating these specific details in select characters.

↳ Ornaments

After we drew a large chunk of the letters, numbers and punctuation, we experimented with ornamentation. We referenced our library of images and pulled some of the more popular ornamentation. There will be more ornamentation in the future.

↳ Final Set

We are also Nigerian lettering artists, and this is our contribution to the Danfo catalogue of typefaces. Special thanks to Mirko for helping with the design approach and construction, Laura for her incredible help with construction, diacritics and this specimen page, Travis and Lizy for their assistance with construction (we conquered that Q!), Thomas and Dave for the opportunity, guidance and platform, Ksenya for construction help, especially around rendering sharp points (we called this Ksenyafication internally haha!) and lastly, to my now disbanded team at Dá Design Studio for encouraging me and making this a worthy endeavour.